Networking the Shahed

Russia’s introduction of datalinks into the Geran-2 is blurring the boundary between loitering munitions and one-way-attack UAVs and is expanding the system’s use beyond pre-programmed targets.

One-Way Routing

The Shahed-136/Geran-2 is frequently mischaracterised as a loitering munition. It is more accurately classified as a one-way-attack UAV (OWA-UAV). While both system types deliver kinetic effects by impact, they differ fundamentally in their control and guidance architectures.

Loitering munitions are equipped with electro-optical sensors, a video downlink and a control uplink that allow real-time operator control as well as attacks on relocatable and moving targets. By contrast, traditional OWA-UAVs operate in an automated mode to reach pre-programmed targets using inertial, satellite and, increasingly, visual navigation systems.

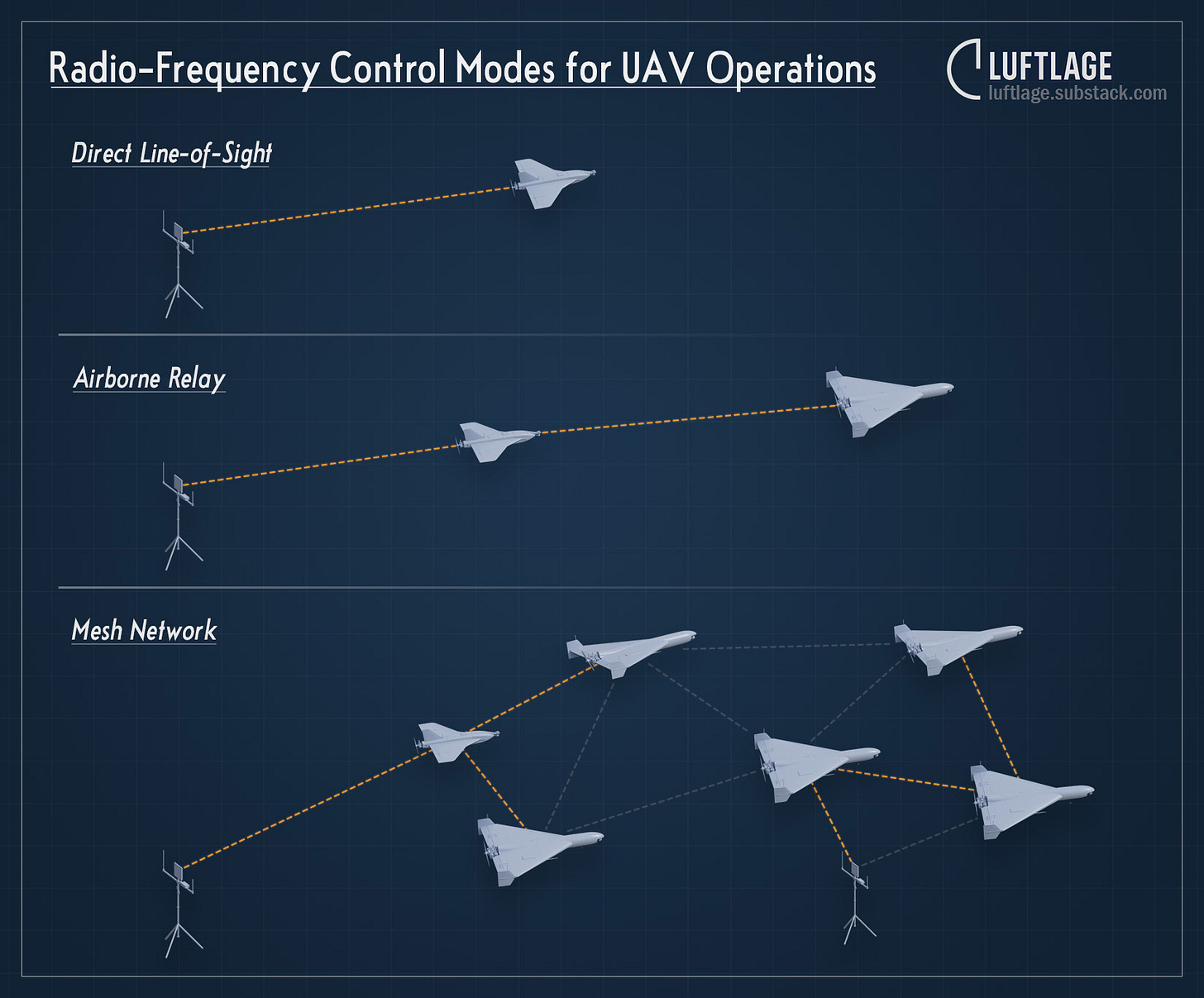

This distinction has significant operational implications. Autonomous inertial and satellite navigation restricts OWA-UAVs to pre-programmed, fixed targets but removes the range constraints associated with line-of-sight control from a ground station. Consequently, whereas most loitering munitions lacking relay support are limited to ranges of several tens of kilometres, OWA-UAVs can achieve ranges of hundreds or even thousands of kilometres allowing for their use in deep strike missions.

Pushing Beyond the Line of Sight

Both Iran and Russia, however, have sought to move beyond the traditional OWA-UAV concept by integrating beyond-line-of-sight (BLOS) datalink options into their platforms. Iran is documented to have used an Iridium satellite phone SIM in a Shahed-series UAV in at least one attack on merchant shipping in 2023. Given the limited bandwidth of this configuration, such links were likely restricted to basic telemetry updates, in-flight retasking, or target-location updates.

While subsequent reporting on Iridium use remains limited, a second and more consequential BLOS option emerged in late 2023, when recovered Geran-2 debris was found to contain SIM cards and associated communications hardware, indicating the ability to connect to Ukraine’s civilian mobile phone network. Whereas these early modifications appeared sporadic and experimental, the design has now been standardized. Today, nearly all observed Geran-2s feature a standard design of flexible PCB antennas for 2G, 3G and 4G services attached to rear stabilizers. The presence of corresponding wingtip cable pass-throughs on Alabuga-produced airframes further suggests a factory-level design choice rather than ad-hoc field modifications.

Yet, despite its prevalence, the precise capability envelope of the Geran-2’s cellular link is still not fully understood. Ukrainian sources assess that it provides an auxiliary positioning capability via cellular base-station triangulation when satellite-navigation is jammed or spoofed. Transmission of basic telemetry data such as position, speed, and altitude also appears likely, given its utility for post-strike assessments, loss tracking, and route optimisation. Leaked Alabuga documents analysed by Ukraine’s Molfar Intelligence Institute further suggest that by 2024 Russia was exploring the transmission of limited ISR outputs, including still imagery, via mobile data, with Telegram bots reportedly serving as data sinks. Whether such arrangements have been adopted at scale remains uncertain.

Crucially, there is no evidence that Russia has achieved sustained real-time operator control of Geran-2 UAVs via mobile networks. While the war in Ukraine has demonstrated that cellular infrastructure can enable temporary operator control for some UAV types, maintaining a stable, low-latency, high-bandwidth mobile internet link for the Geran-2 would pose significant technical challenges, given the system’s mission profile, the inherent limitations of cell phone networks, and potential Ukrainian countermeasures.

Enter the Mesh

More recently, Russia has taken a more substantive step towards providing the Geran-2 with datalink capability by equipping it with mesh network technology. As mentioned above, most UAV radio-frequency datalinks are constrained by the requirement for line-of-sight between the UAV and a ground control station. This constraint, however, can be overcome through airborne relays that establish multiple line-of-sight links. The war in Ukraine has already seen widespread use of such relays, allowing UAVs to extend communication ranges, overcome terrain-induced obstructions, and maintain connectivity at very low altitudes.

Mesh networks take the logic of airborne relays a step further. Rather than relying on linear transmission chains, they make use of a web of distributed nodes that dynamically route traffic and can compensate for the loss or degradation of individual elements.

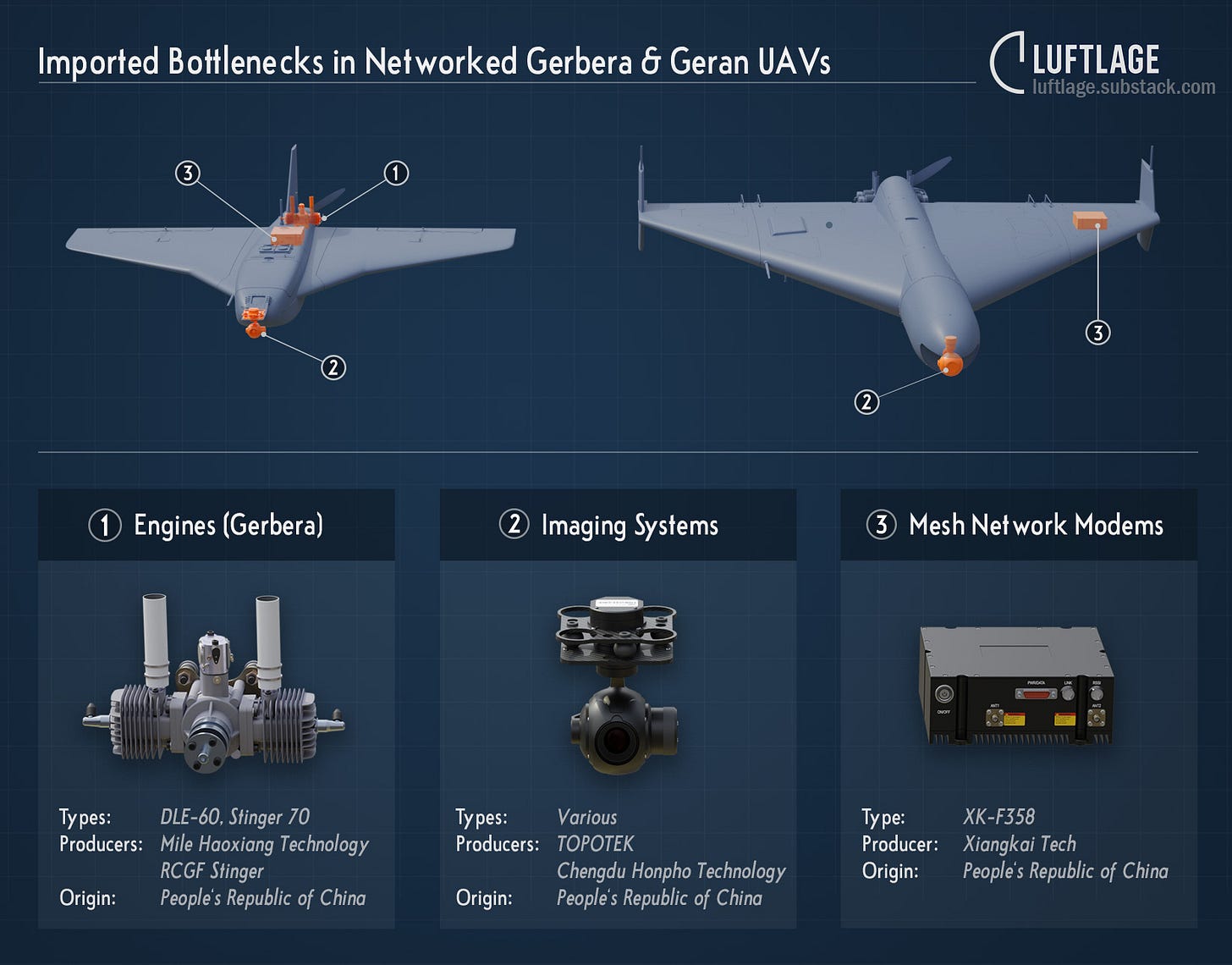

Russia appears to have begun deploying UAV-based mesh networking in 2025, when it equipped the Alabuga-built Gerbera decoy UAV with Chinese-made imaging systems and mesh network modems. The resulting system functioned as a low-cost fixed-wing ISR platform, while also providing practical experience with mesh network-enabled UAV operations. The volume of downed Gerberas configured in this manner, along with the prevalence of mesh network modems for resale on Ukrainian online platforms, suggests the system has been adopted at scale.

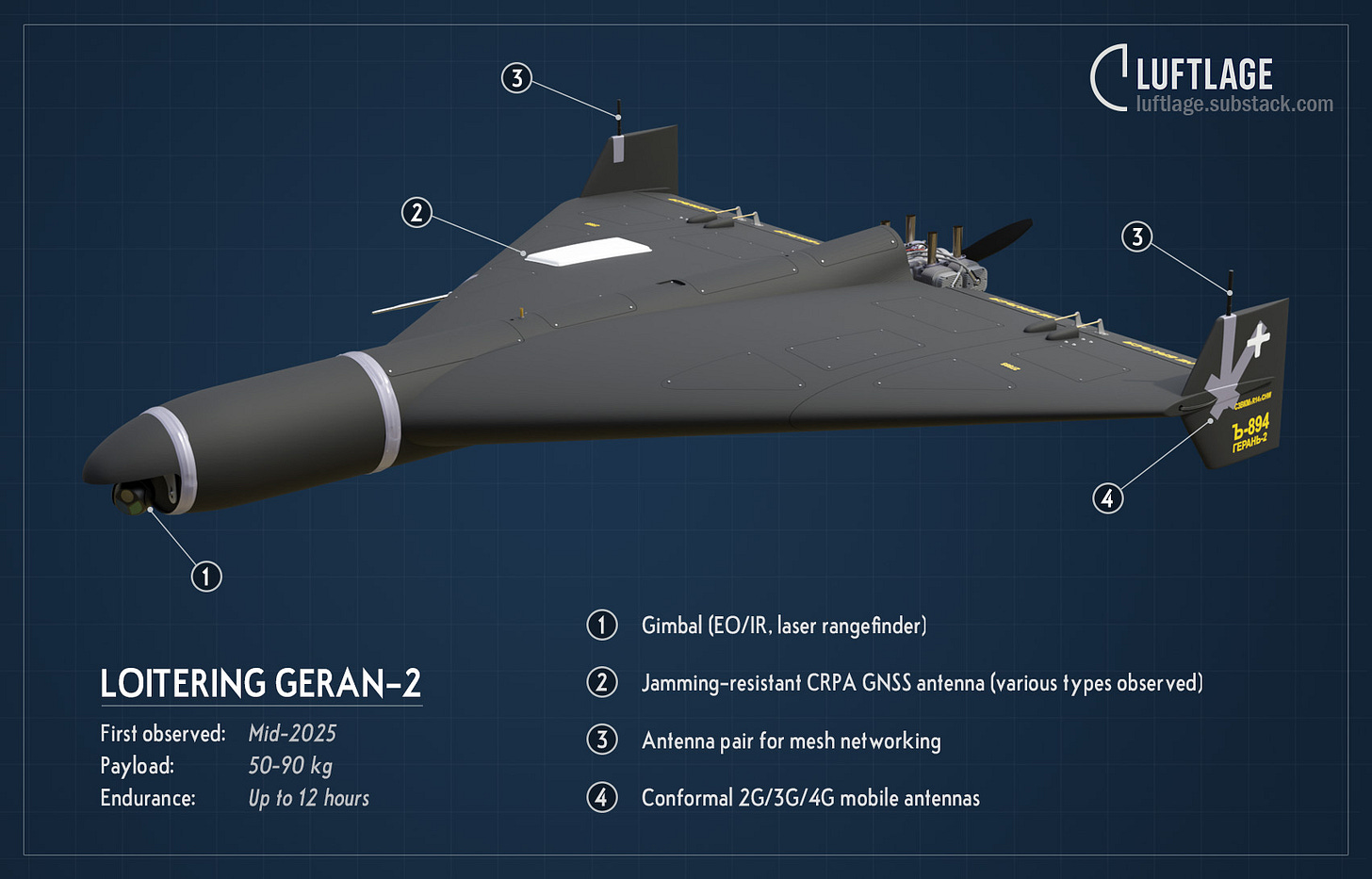

Loitering Shaheds

By mid-2025, Russia had adapted this technology for use on Geran-2 OWA-UAVs. Imagery of recovered debris and in-flight footage emerging around that time showed Geran-2s fitted with the same type of mesh network modems, thermal imagers, and antenna pairs used on ISR Gerbera variants. Taken together, these modifications provide the Geran-2 with both a payload data link and an onboard imaging capability, enabling loitering-munition-style employment with operator control. Notably, this was not Russia’s first consideration of a loitering derivative of the Shahed design. Iran had previously proposed a loitering variant, the Shahed-236, intended to operate in conjunction with an airborne relay. As with jet-powered Shahed variants, however, Russia appears to have declined the Iranian design in favor of developing a domestic solution.

Russia’s domestic loitering Geran-2 variant allowed the country to transform an OWA-UAV system already produced at significant scale into a loitering effector suitable for employment in the mid-range strike role (approximately 50-200km). Over the course of 2025, mid-range strike has assumed increasing prominence as the ‘kill zone’ directly adjacent to the line of contact has become saturated with small UAVs and planners have shifted their attention towards still target-rich areas further to the rear.

There are growing indications that Geran-2 systems are increasingly being employed within this range bracket against operational and even tactical level targets. In recent months, the Russian Ministry of Defence has released a growing volume of footage depicting Geran-2 strikes against military targets in relatively close proximity to the line of contact and in Russian-Ukrainian border areas. In parallel, Ukrainian sources have reported an expanded use of Geran-2s against rear-area logistics targets, including railway infrastructure.

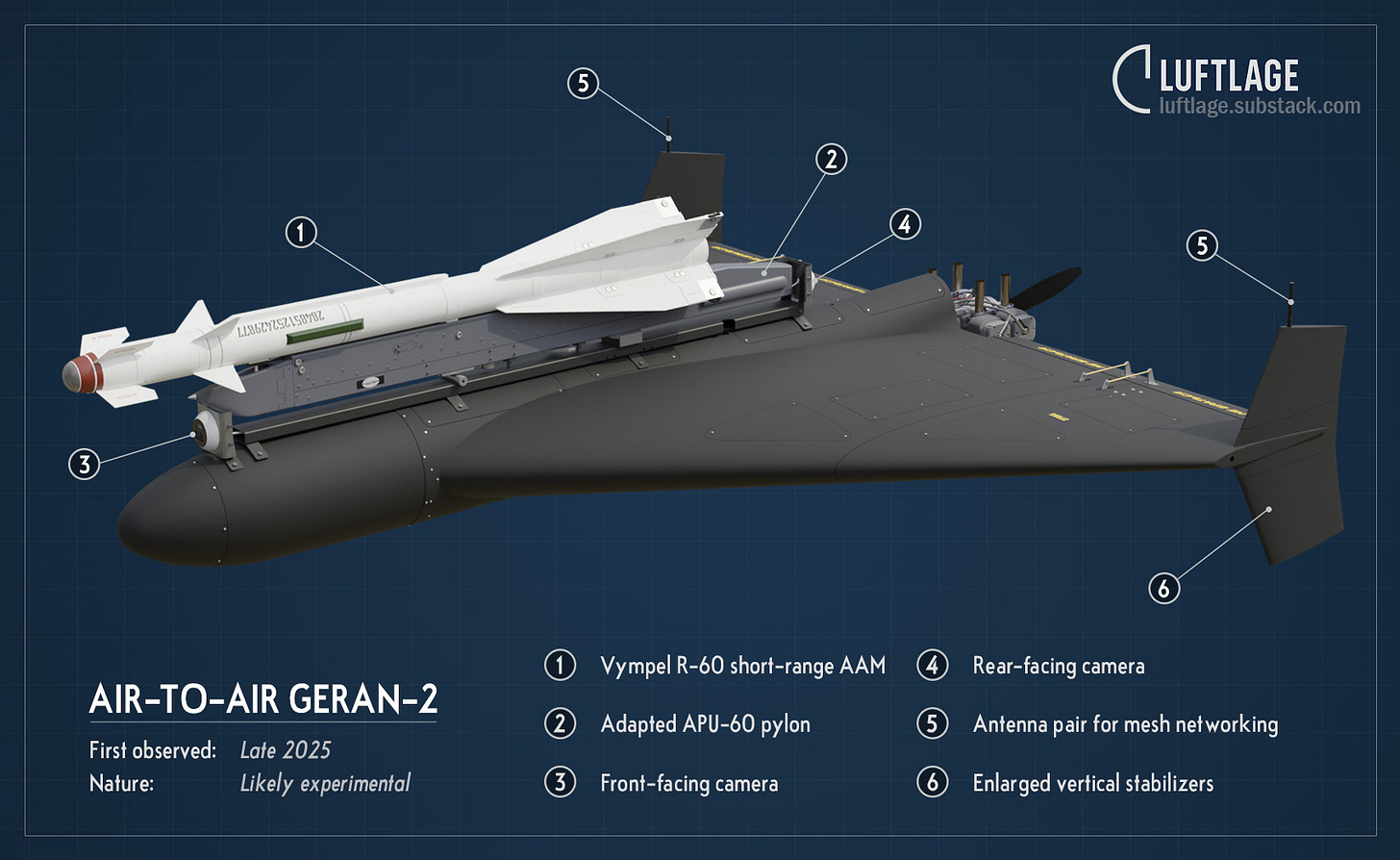

Beyond loitering strike missions, payload data links have also enabled experimentation with other novel concepts of operations. In December 2025 Ukrainian forces intercepted a likely experimental mesh network-enabled Geran-2 carrying a Vympel R-60 (AA-8 Aphid) infrared-homing air-to-air missile. The configuration was likely intended as a countermeasure against Ukrainian fixed-wing and rotary assets tasked with countering OWA-UAVs. Although the reliability and operational utility of this specific configuration remain uncertain, the example illustrates how payload data links can expand the range of feasible system architectures available to OWA-UAVs.

Towards Networked Deep Strike?

While the use of mesh network-enabled Geran-2s as tactical and operational mid-range strike assets is already significant, the maturation of this capability raises the question of whether Moscow is moving toward integrating such systems into its strategic deep-strike campaign against military, industrial, civilian, and critical infrastructure targets deeper inside Ukraine. In such a role, networked Geran-2s would offer improved strike accuracy, persistent stand-in ISR capability, dynamic route optimisation, and the ability to attack relocatable or moving high-value targets, including air-defence systems.

In theory, Russia’s large-scale UAV attack waves, which now routinely involve hundreds of platforms dispersed across Ukraine, would be well suited to networked modes of employment. In practice, effectiveness would be constrained by a variety of factors, including hardware reliability, bandwidth degradation across multiple hops, achievable operational range, the number of nodes that can be managed simultaneously, and the robustness of the overall command and control architecture.

While the operational reliability and scalability of such networked concepts remain uncertain, available evidence indicates that mesh network-enabled Geran-2 variants are already being employed at meaningful distances into Ukraine’s rear.

Loitering Geran-2 systems have been observed in Russia’s intensified strike campaign against Odessa, approximately 70 km from Russian-occupied territory, including an incident on 12 December 2025 in which a loitering Geran-2 struck the Turkish RoRo vessel Cenk T. On 22-23 December, a Geran-2 reportedly struck a moving train near Korosten in Zhytomyr Oblast, roughly 80km from the Belarusian border. On 25 December, a Russian Telegram channel published undated footage apparently recorded by loitering Geran-2s targeting energy infrastructure in Chernihiv Oblast. Two of the strikes near Pryluky occurred at distances of approximately 140 km from either the Belarusian or Russian border.

Beyond the attacks outlined above, additional visual evidence also suggests that mesh network-enabled Geran-2s are employed with increasing frequency. Interception footage released by the Ukrainian interceptor UAV manufacturer Wild Hornets shows a growing number of Geran-2s fitted with the distinctive antenna pair associated with loitering variants. In several instances, this configuration has also been observed on jet-powered Geran-3 systems.

Alongside airborne mesh networked nodes, Ukrainian officials and technical specialists have highlighted the potential role of additional ground-based infrastructure in supporting loitering Geran-2 operations.

Only days after the reported Geran-2 strike on a moving train in Zhytomyr Oblast, President Volodymyr Zelensky stated that Russia had installed control or relay stations on the roofs of residential buildings in Belarusian border areas. Achieving a ground-to-UAV communications range of approximately 200 km would be broadly consistent with concepts previously marketed by Iran for Shahed-236 operations conducted in conjunction with airborne relays. If such ranges can be realised by Russia, the deployment of stations in Belarus, occupied Ukrainian territory, and potentially Transnistria would enable coverage of significant areas of Ukrainian government-controlled territory. Ukrainian electronic warfare specialist Serhii Beskrestnov has warned that these capabilities could be further augmented through the covert deployment of ground-based relay nodes within Ukrainian-held territory itself.

New Capabilities, New Vulnerabilities?

While equipping Geran-2s with a payload data link allows new concepts of employment, these enhanced capabilities also impose additional costs and present new vulnerabilities. Mesh network modems of the type observed on Gerbera and Geran-2 UAVs, along with high-quality EO/IR imaging systems, typically trade for thousands of dollars. Their integration therefore measurably increases the unit cost of the Geran-2, which Ukrainian intelligence currently assesses at approximately USD 70,000 per system.

The risk of supply-chain disruption represents a further latent cost. Unlike many other foreign-sourced components used in Geran systems, such as low-cost and widely available commercial off-the-shelf electronic components, mesh network modems and imaging payloads constitute highly specialised subsystems produced by only a limited number of manufacturers. Observed modems appear to originate from a single producer, suggesting that large-scale substitution in the event of supply-chain disruption would likely prove challenging.

Further vulnerabilities arise in the electronic warfare domain. Traditional Geran-2s, relying on satellite navigation, have long been subject to Ukrainian jamming and spoofing. In response, Russia has steadily improved its jamming-resistant satellite navigation antenna systems, which are generally assessed to perform effectively. Whether Russia’s mesh network data links will demonstrate comparable resilience under combat conditions remains uncertain.

Blurred Lines, Emerging Threats

The rapid evolution of UAV technology in the context of the war in Ukraine has increasingly eroded conceptual boundaries between system categories once considered distinct. Russia’s adoption of BLOS-capable Geran-2 variants, which straddle the line between OWA-UAVs and loitering munitions, is another case in point.

Current developments in communications technology suggest that the move towards loitering-capable long-range OWA-UAVs is only going to accelerate and will not remain confined to the use of mesh networks. Proliferated low Earth orbit satellite communication systems, paired with compact user terminals, offer potentially even more robust BLOS data links for OWA-UAVs. The United States has already introduced the Shahed 136-inspired Low-Cost Uncrewed Combat Attack System (LUCAS), equipped with a Starlink Mini terminal, enabling high-bandwidth satellite communications over effectively unlimited ranges. Russia, for its part, is also attempting to adapt Starlink for fixed-wing UAV-use and could, in the future, benefit from alternative satellite constellations not subject to US regulatory constraints.

Ukrainian and Western defence planners must therefore contend with the fact that their adversaries’ OWA-UAVs are becoming both more capable and more versatile. Most significantly, the emergence of networked Shahed variants demonstrates that OWA-UAVs do not constitute a static threat against which defenders can simply catch up. Rather, like UAV classes, they are subject to rapid tactical and technological evolution, including changes substantial enough to alter the underlying concept of operations.